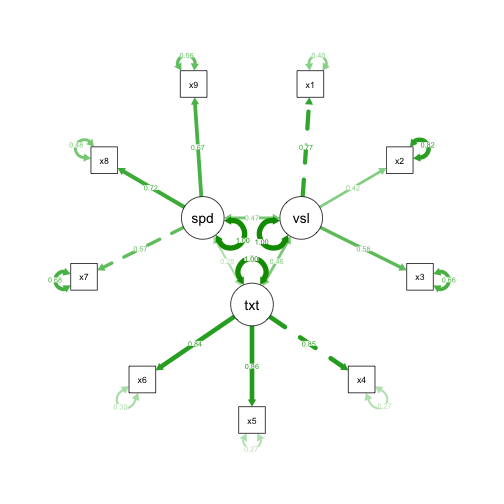

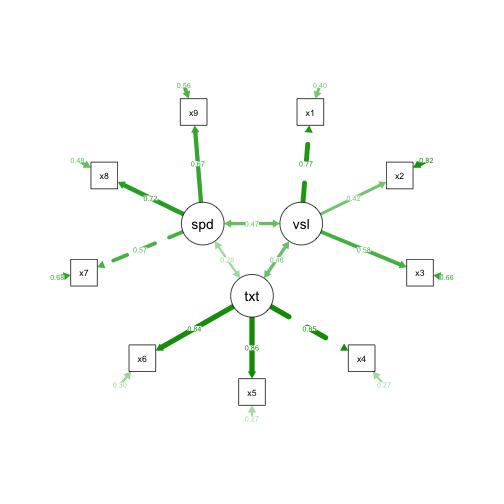

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Lecture 8: PY 0794 - Advanced Quantitative Research Methods ] .author[ ### Dr. Thomas Pollet, Northumbria University (<a href="mailto:thomas.pollet@northumbria.ac.uk" class="email">thomas.pollet@northumbria.ac.uk</a>) ] .date[ ### 2025-03-17 | <a href="http://tvpollet.github.io/disclaimer">disclaimer</a> ] --- ## PY0794: Advanced Quantitative research methods. * Last lecture: Exploratory Factor analysis * Today: SEM I: Confirmatory Factor analysis. --- ## Goals (today) Lavaan. CFA sem. Not: Make you a 'sem' expert. That would take an entire separate course, but you should be able to apply the basics and understand when you come across it. --- ## Assignment After today you should be able to complete the following sections for Assignment II: Confirmatory Factor Analysis via SEM. --- ## Last week. Last week we covered exploratory factor analysis Factor analysis is used to find a set of unobserved variables (latent variables / dimensions) which account for the covariance among a larger set of observed variables (manifest variables or indicators). Basically, we have a large number of questions and we want to reduce the complexity. Think back to the personality example of last week. --- ## Why is this useful? Mostly: Questionnaire validation. How many dimensions? Are they same or different across groups? Can we drop questions? Generate scores which discriminate between participants. --- ## EFA vs. CFA. EFA has a lot of potential for ambiguous decisions. (How many to extract, How to extract, cut-offs for removing bad items.). CFA forces you to make more explicit decisions. Explicit tests for which models are better. --- ## Terms. Observed variable (indicator/manifest variable): it is something you measured. Examples: a question on a happiness questionaire, a question about personality. Denoted with a rectangle. Latent variable (construct/unobserved variable): we assume that these are the underlying variables causing people to score high or low on our observed variables. Examples: Well-being, Openness, Intelligence. Denoted with a circle. --- ## More terms Covariances: Denoted with double-headed arrows Residuals: "the trash bag", for which we can estimate the variance. We can allow them to be correlated or not. Useful to examine. Double-headed arrow to observed variable. --- ## How is it done? Matrix algebra. We can recast all proposed relations into a big matrix and then (attempt) to solve that matrix. <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/l2Ject9fem5QZOyTC/giphy.gif" width="500px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Lavaan / sem Outside of R there are specific packages which can do SEM, most notably MPLus, Lisrel, Latentgold, AMOS. But here you would have to leave SPSS for a different package. There are also multiple packages in R which can do SEM (OpenMX, sem, Lavaan). Today we will focus on Lavaan. --- ## Example. ?HolzingerSwineford1939. Data on children's performance in two schools. (a subset) <img src="https://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/cfa_files/figure-html/cfa-1.png" width="380px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Notations in Lavaan. Regressions: f= factor (latent variable) y ~ f1 + f2 + x1 + x2 f1 ~ f2 + f3 f2 ~ f3 + x1 + x2 Factors. f1 =~ y1 + y2 + y3 f2 =~ y4 + y5 + y6 f3 =~ y7 + y8 + y9 + y10 --- ## Notations. Double tildes for variance and covariances. y1 ~~ y1 # variance y1 ~~ y2 # covariance f1 ~~ f2 # covariance Intercepts. ~ 1 y1 ~ 1 f1 ~ 1 --- ## Back to our example. visual =~ x1 + x2 + x3 textual =~ x4 + x5 + x6 speed =~ x7 + x8 + x9 <img src="https://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/cfa_files/figure-html/cfa-1.png" width="380px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Our model in lavaan. In order to define the model we place it in-between single (!) quotes. We can annotate with # ``` r require(lavaan) Model_1 <- " # Three factors. visual =~ x1 + x2 + x3 textual =~ x4 + x5 + x6 speed =~ x7 + x8 + x9 " ``` --- ## Assumptions. Before we move further: consider assumptions! Basically, we are dealing with regressions (and factor analyses are a variant of that). If there are no meaningful correlations, then it makes little sense to perform CFA. So one would usually examine or plot those. One way is to use the KMO test which we used last time. ``` r require(psych) f_data <- (lavaan::HolzingerSwineford1939)[, c(7:15)] KMO(f_data) ``` ``` ## Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin factor adequacy ## Call: KMO(r = f_data) ## Overall MSA = 0.75 ## MSA for each item = ## x1 x2 x3 x4 x5 x6 x7 x8 x9 ## 0.81 0.78 0.73 0.76 0.74 0.81 0.59 0.68 0.79 ``` --- ## Assumptions. Caution, not multivariate normal. One solution is robust estimation... . Maximum Likelihood (ML) more robust than some other methods but still cautious (affects standard errors of paths). ``` r require(MVN) mvn(f_data, multivariatePlot = "qq") ``` <img src="Lecture8_xaringan_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ``` ## $multivariateNormality ## Test HZ p value MVN ## 1 Henze-Zirkler 1.054447 1.761547e-07 NO ## ## $univariateNormality ## Test Variable Statistic p value Normality ## 1 Anderson-Darling x1 0.6012 0.1176 YES ## 2 Anderson-Darling x2 3.3140 <0.001 NO ## 3 Anderson-Darling x3 4.1332 <0.001 NO ## 4 Anderson-Darling x4 2.1482 <0.001 NO ## 5 Anderson-Darling x5 1.9650 1e-04 NO ## 6 Anderson-Darling x6 3.3025 <0.001 NO ## 7 Anderson-Darling x7 0.9839 0.0133 NO ## 8 Anderson-Darling x8 0.8153 0.0347 NO ## 9 Anderson-Darling x9 0.1633 0.9435 YES ## ## $Descriptives ## n Mean Std.Dev Median Min Max 25th 75th ## x1 301 4.935770 1.167432 5.000000 0.6666667 8.500000 4.166667 5.666667 ## x2 301 6.088040 1.177451 6.000000 2.2500000 9.250000 5.250000 6.750000 ## x3 301 2.250415 1.130979 2.125000 0.2500000 4.500000 1.375000 3.125000 ## x4 301 3.060908 1.164116 3.000000 0.0000000 6.333333 2.333333 3.666667 ## x5 301 4.340532 1.290472 4.500000 1.0000000 7.000000 3.500000 5.250000 ## x6 301 2.185572 1.095603 2.000000 0.1428571 6.142857 1.428571 2.714286 ## x7 301 4.185902 1.089534 4.086957 1.3043478 7.434783 3.478261 4.913043 ## x8 301 5.527076 1.012615 5.500000 3.0500000 10.000000 4.850000 6.100000 ## x9 301 5.374123 1.009152 5.416667 2.7777778 9.250000 4.750000 6.083333 ## Skew Kurtosis ## x1 -0.2543455 0.30753382 ## x2 0.4700766 0.33239397 ## x3 0.3834294 -0.90752645 ## x4 0.2674867 0.08012676 ## x5 -0.3497961 -0.55253689 ## x6 0.8579486 0.81655717 ## x7 0.2490881 -0.30740386 ## x8 0.5252580 1.17155564 ## x9 0.2038709 0.28990791 ``` --- ## Test. ``` r require(MVN) mvn(f_data) ``` ``` ## $multivariateNormality ## Test HZ p value MVN ## 1 Henze-Zirkler 1.054447 1.761547e-07 NO ## ## $univariateNormality ## Test Variable Statistic p value Normality ## 1 Anderson-Darling x1 0.6012 0.1176 YES ## 2 Anderson-Darling x2 3.3140 <0.001 NO ## 3 Anderson-Darling x3 4.1332 <0.001 NO ## 4 Anderson-Darling x4 2.1482 <0.001 NO ## 5 Anderson-Darling x5 1.9650 1e-04 NO ## 6 Anderson-Darling x6 3.3025 <0.001 NO ## 7 Anderson-Darling x7 0.9839 0.0133 NO ## 8 Anderson-Darling x8 0.8153 0.0347 NO ## 9 Anderson-Darling x9 0.1633 0.9435 YES ## ## $Descriptives ## n Mean Std.Dev Median Min Max 25th 75th ## x1 301 4.935770 1.167432 5.000000 0.6666667 8.500000 4.166667 5.666667 ## x2 301 6.088040 1.177451 6.000000 2.2500000 9.250000 5.250000 6.750000 ## x3 301 2.250415 1.130979 2.125000 0.2500000 4.500000 1.375000 3.125000 ## x4 301 3.060908 1.164116 3.000000 0.0000000 6.333333 2.333333 3.666667 ## x5 301 4.340532 1.290472 4.500000 1.0000000 7.000000 3.500000 5.250000 ## x6 301 2.185572 1.095603 2.000000 0.1428571 6.142857 1.428571 2.714286 ## x7 301 4.185902 1.089534 4.086957 1.3043478 7.434783 3.478261 4.913043 ## x8 301 5.527076 1.012615 5.500000 3.0500000 10.000000 4.850000 6.100000 ## x9 301 5.374123 1.009152 5.416667 2.7777778 9.250000 4.750000 6.083333 ## Skew Kurtosis ## x1 -0.2543455 0.30753382 ## x2 0.4700766 0.33239397 ## x3 0.3834294 -0.90752645 ## x4 0.2674867 0.08012676 ## x5 -0.3497961 -0.55253689 ## x6 0.8579486 0.81655717 ## x7 0.2490881 -0.30740386 ## x8 0.5252580 1.17155564 ## x9 0.2038709 0.28990791 ``` --- ## CFA ``` r require(lavaan) fit <- cfa(Model_1, data = HolzingerSwineford1939) sink(file = "summary_fit.txt") summary(fit, fit.measures = TRUE) sink() ``` --- ## Some familiar faces... . The TLI suggested an acceptable fit (.9), as did the CFI (.93). However, the RMSEA (.092) suggested a relatively poor fit with a 90%CI ranging from .071 to .114. The CFI is another fit measure, some argue >.9, some argue >.95. read more [here](https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/297019805.pdf). Many measures exist, most commonly reported RMSEA,CFI,TLI <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/yUVDwTU9KAMFO/giphy.gif" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Try it yourself. Return to last week's model which we tested in class. (If you failed to save your datafile, you can download it again from [here](https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/M255.sav)) Write a three factor model in lavaan's format and evaluate the fit measures. <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/ArrVyXcjSzzxe/giphy.gif" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Visualise and interpret. ``` r require(semPlot) semPaths(fit, layout = "circle", style = "ram", what = "std") ``` <!-- --> --- ## Lisrel style plot. ``` r semPaths(fit, layout = "circle", style = "lisrel", what = "std") ``` <!-- --> --- ## Try it yourself! Make a plot of your three-factor model. <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/mpbcL7277vXqM/giphy.gif" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Export a table. ``` r require(dplyr) require(stargazer) results_table <- parameterEstimates(fit, standardized = TRUE) %>% filter(op == "=~") %>% dplyr::select(`Latent Factor` = lhs, Indicator = rhs, B = est, SE = se, Z = z, `p value` = pvalue, Beta = std.all) # export via stargazer. (Other options are # ??xtable) stargazer(results_table, summary = FALSE, out = "results_table.html", header = F) ``` ``` ## ## \begin{table}[!htbp] \centering ## \caption{} ## \label{} ## \begin{tabular}{@{\extracolsep{5pt}} cccccccc} ## \\[-1.8ex]\hline ## \hline \\[-1.8ex] ## & Latent Factor & Indicator & B & SE & Z & p value & Beta \\ ## \hline \\[-1.8ex] ## 1 & visual & x1 & $1$ & $0$ & $$ & $$ & $0.772$ \\ ## 2 & visual & x2 & $0.554$ & $0.100$ & $5.554$ & $0.00000$ & $0.424$ \\ ## 3 & visual & x3 & $0.729$ & $0.109$ & $6.685$ & $0$ & $0.581$ \\ ## 4 & textual & x4 & $1$ & $0$ & $$ & $$ & $0.852$ \\ ## 5 & textual & x5 & $1.113$ & $0.065$ & $17.014$ & $0$ & $0.855$ \\ ## 6 & textual & x6 & $0.926$ & $0.055$ & $16.703$ & $0$ & $0.838$ \\ ## 7 & speed & x7 & $1$ & $0$ & $$ & $$ & $0.570$ \\ ## 8 & speed & x8 & $1.180$ & $0.165$ & $7.152$ & $0$ & $0.723$ \\ ## 9 & speed & x9 & $1.082$ & $0.151$ & $7.155$ & $0$ & $0.665$ \\ ## \hline \\[-1.8ex] ## \end{tabular} ## \end{table} ``` --- ## Interpretation. Most load above >.45 and quite high. Hurray! Some further decision rules: [here](http://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/thresholds) Some rules of thumb for factor loadings: some use .4 or .5 as a cut-off, others argue for this range 0.32 (poor), 0.45 (fair), 0.55 (good), 0.63 (very good) or 0.71 (excellent), but beware of cut-offs in general. --- ## Residuals check. Mostly weak to no correlations (<.3 in absolute size). Hurray, again! You could also still check the distributions of those. ``` r require(ggplot2) require(corrplot) plot_matrix <- function(matrix_toplot) { corrplot(matrix_toplot, is.corr = FALSE, type = "lower", order = "original", tl.col = "black", tl.cex = 0.75) } plot_matrix(residuals(fit)$cov) ``` <img src="Lecture8_xaringan_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-16-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Single factor model. ``` r require(lavaan) Model_2 <- " # one factor. ability =~ x1 + x2 + x3 + x4 + x5 + x6 + x7 + x8 + x9 " ``` --- ## Text output. ``` r fit_model_2 <- cfa(Model_2, data = HolzingerSwineford1939) sink(file = "summary_fit_2.txt") summary(fit_model_2, fit.measures = T) sink() ``` --- ## Compare fit. AIC and BIC are fit indices. BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) penalizes model complexity more harshly than AIC. Lower is better. (The rationale is information theory, which you can read about [here](http://ecologia.ib.usp.br/bie5782/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=bie5782:pdfs:burnham_anderson2002.pdf)) Many guidelines on fit indices, read more [here](http://ecologia.ib.usp.br/bie5782/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=bie5782:pdfs:burnham_anderson2002.pdf). You can also generate [AIC weights](http://ejwagenmakers.com/2004/aic.pdf). --- ## Interpretation. Some rules of thumb from Kass & Raftery (1995) (based on BIC). (Again apply sensibly... .) 0 to 2: Not worth more than a bare mention 2 to 6: Positive 6 to 10: Strong \>10: Very Strong --- ## Fit. A model with three factors is a better fit to the data than one with a single factor in terms of AIC and BIC (both `\(\Delta\geq\)` 205). --> this means overwhelming support for the three factor solution. ``` r anova(fit, fit_model_2) ``` ``` ## ## Chi-Squared Difference Test ## ## Df AIC BIC Chisq Chisq diff RMSEA Df diff Pr(>Chisq) ## fit 24 7517.5 7595.3 85.305 ## fit_model_2 27 7738.4 7805.2 312.264 226.96 0.49801 3 < 2.2e-16 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- ## Try it yourself. Make a one factor model for the Sidanius data. Compare the fit of that model to a three-factor model. What do you conclude? --- ## Measurement invariance? Have you heard of the term? Can you think of situations where it would be useful? --- ## Measurement invariance. Is the pattern the same for certain groups? Read more [here](http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740) 1) Equal form: The number of factors and the pattern of factor-indicator relationships are identical across groups. 2) Equal loadings: Factor loadings are equal across groups. 3) Equal intercepts: When observed scores are regressed on each factor, the intercepts are equal across groups. 4) Equal residual variances: The residual variances of the observed scores not accounted for by the factors are equal across groups --> all 4 satisfied: **strict** measurement invariance. This does not always happen. --- ## Our example. Let's compare if the three-factor structure is the same in both schools. Basically: Is the measurement in both schools the same? <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/vVKqa0NMZzFyE/giphy.gif" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Group model ``` r require(lavaan) Data <- HolzingerSwineford1939 Group_model_1 <- " # Three factors. visual =~ x1 + x2 + x3 textual =~ x4 + x5 + x6 speed =~ x7 + x8 + x9 " fit_CFA_group <- cfa(Group_model_1, data = Data, group = "school") ``` --- ## Massive output! ``` r sink(file = "group_cfa.txt") summary(fit_CFA_group, fit.measures = T) sink() ``` <img src="https://media.giphy.com/media/qYW82HZYn7fOM/giphy.gif" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Plot. Combined groups plot. ``` r require(semPlot) require(qgraph) semPaths(fit_CFA_group, layout = "circle", style = "ram", what = "std", combineGroups = T) ``` <img src="Lecture8_xaringan_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-24-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Separate plots. ``` r require(semPlot) require(qgraph) semPaths(fit_CFA_group, layout = "circle", style = "ram", what = "std", combineGroups = F) ``` <img src="Lecture8_xaringan_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /><img src="Lecture8_xaringan_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-2.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Measurement Invariance ``` r require(semTools) semTools::measurementInvariance(model = Group_model_1, data = Data, group = "school") ``` ``` ## ## Measurement invariance models: ## ## Model 1 : fit.configural ## Model 2 : fit.loadings ## Model 3 : fit.intercepts ## Model 4 : fit.means ## ## ## Chi-Squared Difference Test ## ## Df AIC BIC Chisq Chisq diff RMSEA Df diff Pr(>Chisq) ## fit.configural 48 7484.4 7706.8 115.85 ## fit.loadings 54 7480.6 7680.8 124.04 8.192 0.049272 6 0.2244 ## fit.intercepts 60 7508.6 7686.6 164.10 40.059 0.194211 6 4.435e-07 ## fit.means 63 7543.1 7710.0 204.61 40.502 0.288205 3 8.338e-09 ## ## fit.configural ## fit.loadings ## fit.intercepts *** ## fit.means *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## ## Fit measures: ## ## cfi rmsea cfi.delta rmsea.delta ## fit.configural 0.923 0.097 NA NA ## fit.loadings 0.921 0.093 0.002 0.004 ## fit.intercepts 0.882 0.107 0.038 0.015 ## fit.means 0.840 0.122 0.042 0.015 ``` --- ## Terminology. Model 2: Metric invariance: "Respondents across groups attribute the same meaning to the latent construct under study" Model 3: Scalar invariance: "implies that the meaning of the construct (the factor loadings), and the levels of the underlying items (intercepts) are equal in both groups. Consequently, groups can be compared on their scores on the latent variable." Model 4: Strict invariance: "means that the explained variance for every item is the same across groups. Put more strongly, the latent construct is measured **identically** across groups" More [here](http://users.ugent.be/~yrosseel/lavaan/multiplegroup6Dec2012.pdf) and [here](http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740) --- ## Table. Stargazer won't change labels! See if you can figure out a solution :). it cost me a day... . ``` r require(psytabs) require(stargazer) MI <- measurementInvariance(model = Group_model_1, data = Data, group = "school") tab.1 <- measurementInvarianceTable(MI) stargazer(tab.1, summary = F, type = "html", dep.var.labels = c("$\\chi^2$", "df", "$\\Delta$\\chi^2$", "df", "p", "CFI", "$\\Delta$CFI", "RMSEA", "$\\Delta$RMSEA", "BIC", "$\\Delta$BIC"), out = "Measurement invariance.html", header = F) ``` --- ## Sample write up. The best fitting model based on both AIC and BIC was one with metric invariance (respectively 7480.6 and 7680.6). In terms of RMSEA the model with metric invariance and that with configural invariance scored lowest. CFI favoured the configural model (0.923) but the difference with the metric invariance model was small (<.001). While the metric invariance model is not an adequate fit (.093) in terms of RMSEA, it is in CFI (.92). Both the `\(\Delta\)`CFI and `\(\Delta\)`RMSEA suggested that there was no loss in fit moving from a configural model to a metric invariance model (all <.002). In conclusion: Metric Invariance in this case: "the meaning is the same across both groups". --- ## Partial invariance. It is possible that the lack of measurement invariance is caused by issues with just one or two items. In such a case, we could allow those to 'vary' between the groups. You can read more [here](http://users.ugent.be/~yrosseel/lavaan/multiplegroup6Dec2012.pdf) --- ## Exercise Using the 'bfi' data from the 'psych' package, build a five factor model using lavaan. Discuss the CFI, RMSEA and TLI of that model. Export a table with the factor loadings. Make a plot. Compare the fit of a five factor model to a single factor model ("The general factor of personality"). --- ## Exercise (cont'd) Test the measurement invariance for men vs. women in the five factor model. Make a plot. Make a table and discuss. --- ## References (and further reading.) Also check the reading list! (many more than listed here). * Beaujean, A. A. (2014). _Latent variable modeling using R: A step-by-step guide_. Routledge. * Hoyle, R. H. (ed.) (2014). _Handbook of Structural Equation Modelling._ London, UK: Guilford. * Loehlin, J. C., & Beaujean, A. A. (2017). _Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis_. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. * Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. _Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2)_, 1-36. also [see this](http://lavaan.ugent.be). * UCLA advanced research computing (2022). _Confirmatory factor analysis in R with lavaan._ https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/r/seminars/rcfa/ * Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. _European Journal of Developmental Psychology_, 9(4), 486–492. * Van de Schoot, R. & Schalken, N. (2017). Lavaan: how to get started. https://www.rensvandeschoot.com/tutorials/lavaan-how-to-get-started/ * Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. (2007) _Using Multivariate Statistics._ Boston, MA.: Pearson Education.